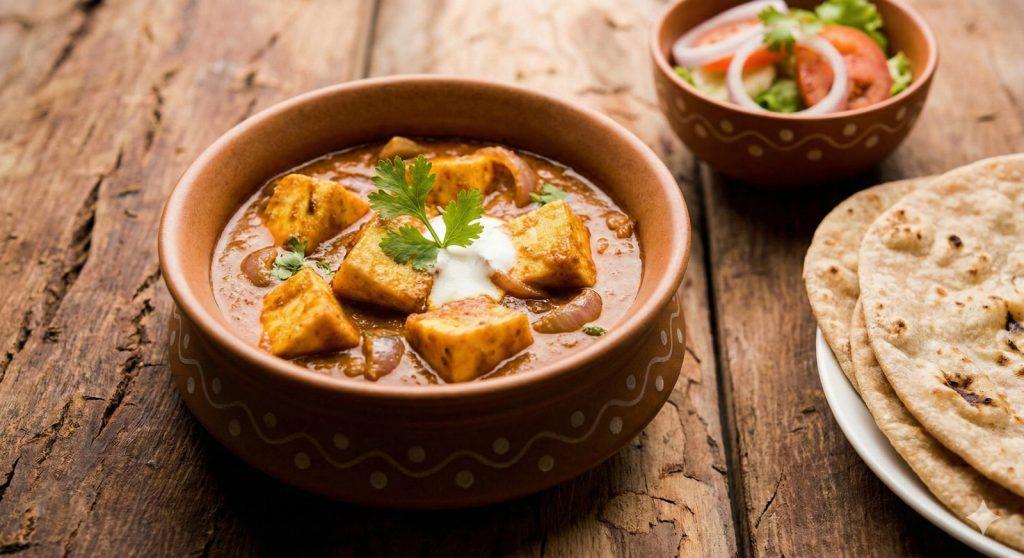

There are dishes that enter your life quietly. You don’t remember the first time you ate them or who cooked them or why they happened to be on the table that day. Paneer Do Pyaza is one of those dishes for me. It has always felt like something that belonged in the background while conversations happened around it. Maybe that’s why it has stayed in so many kitchens for so long and it’s familiar without being predictable.

When I think of it, I picture a late Sunday afternoon in a North Indian home. The kind where the ceiling fan hums louder than it should, and someone is moving around the kitchen with no real urgency. There are onions on the chopping board, more onions than you think you need and a block of paneer resting in a bowl of water. Nothing about the scene suggests a “special” recipe. And yet, by the time everything comes together, the dish feels oddly complete, like it knew what it was doing from the very beginning.

That, in a way, is the heart of Paneer Do Pyaza. It doesn’t show off. It doesn’t claim to be a rich Mughlai masterpiece or a restaurant classic. It sits firmly in the middle, warm, comforting, gently layered and somehow ends up being memorable without trying.

Where the Dish Comes From (Or What We Think We Know)

If you ask ten people where Paneer Do Pyaza started, you’ll hear ten different versions. Some will tell you it was a Mughal invention adapted over time. Others will insist it’s just a home-born recipe that grew popular because onions were cheap and paneer was always around.

The truth is probably somewhere in between. Early “do pyaza” dishes were made with meat which is slow-cooked, indulgent, deep in flavour. But as paneer became a central part of vegetarian households, cooks began adapting their favourite gravies to suit it. That’s how this version likely came to be — not through restaurants or chefs, but through trial and error in hundreds of homes.

What hasn’t changed is the idea of “double onions.” One set dissolves into the gravy, the other stands tall in chunky layers. Together, they create a kind of push and pull softness on one side, bite on the other.

The Ingredients That Make It Work (More Than They Appear To)

Paneer

You can tell a good paneer dish within seconds. If the paneer is soft and holds its shape, the dish feels a little more alive. If it’s rubbery, nothing can save it. That’s why a lot of home cooks soak paneer in hot water for a few minutes before using it, a small trick, but it works.

Onions

The real star. One batch chopped fine so it disappears into the masala; another sliced lengthwise so it remains visible. There’s something almost poetic about how the same ingredient behaves differently depending on how you treat it.

Tomatoes

Used sparingly here. They give the gravy a gentle tang, not the bold acidity you find in restaurant curries.

Yogurt

Just enough to soften the edges. It rounds off the flavour without weighing the dish down.

Spices

Nothing fancy. Nothing unusual. Just the dependable things you’d expect to find in most Indian kitchens.

Kasuri Methi

This is where minimalism stops. A pinch of crushed fenugreek leaves changes the character of the dish instantly. Without it, Paneer Do Pyaza tastes incomplete, like a sentence missing a word you can’t quite place.

Ingredients For Paneer Do Pyaza :-

- Paneer – 200 gram

- Onion – 2 big size ( finely chopped)

- Tomato- 2 big

- Cashew nut.- 12 – 15 pieces

- Oil (as per requirement)

- Turmeric powder- 1 teaspoon

- Red chilli powder- 2 tsp

- Cumin powder- 1teaspoon

- Black paper. – ½ teaspoon

- Salt – ( according to taste)

- Garam masala – ½ tablespoon

- Kasuri Methi (optional)

Note : Some extra onions and capsicum required and chopped them in big sizes.

The Cooking Itself: Slow, Simple, and Surprisingly Therapeutic

If you’ve ever cooked on a day when your mind was scattered, you’ll understand how grounding this process feels. First, the bite of onions as you slice them. Then the sound of cumin hitting hot oil. Then the shift in aroma as tomatoes break down and blend into the masala.

There’s a rhythm to it.

The base onions cook slowly, turning soft and golden. That step can’t be rushed. Raw-tasting onions can ruin the dish. Once the masala begins to release oil, everything feels like it’s moving in the right direction.

The paneer goes in gently. It doesn’t need aggression. A light stir is enough.

Somewhere during this, you sauté the sliced onions in a separate pan. The goal isn’t browning; it’s softness with just a hint of crunch. When these onions meet the gravy, they bring the dish its name and its personality.

Kasuri methi and garam masala come at the end. A five-minute rest after cooking allows everything to settle and become what it’s supposed to be.

Why the Dish Still Holds Its Place on the Table

Paneer Do Pyaza survives because it doesn’t demand anything from you. You can serve it with roti if that’s what you have. Or naan, if you’re feeling indulgent. Or rice, if you want comfort without effort. It fits in everywhere.

What makes it beautiful is the balance – not too spicy, not too rich, not too plain. A little sweet from onions, a little tangy from tomatoes, a little earthy from kasuri methi. Soft paneer against firm onions. Familiar spices behaving with restraint.

It’s the kind of dish that never feels out of place.

A Few Things Home Cooks Learn Over Time

- Let onions cook longer than you think.

- Avoid frying paneer too much; it becomes chewy.

- Yogurt must go in slowly, and only on low heat.

- Kasuri methi isn’t optional, it’s defining.

- Rest the dish before serving; the flavours settle better.

None of these are strict rules, but they come from experience — the kind that human cooks collect over years, not algorithms.

In the End, It’s a Dish That Feels Like Home

A lot of Indian recipes impress you with richness or heat or complexity. Paneer Do Pyaza impresses you quietly. You taste it and think, “I’ve had this before,” even if you haven’t. It carries echoes of home kitchens, of slow afternoons, of familiar smells drifting down hallways.

Perhaps that’s why it remains, decade after decade, one of the dishes people return to. Not because it’s extraordinary in any dramatic sense, but because it feels like it has always been part of the table.

And that, more than anything else, is what gives food its power — the ability to comfort without announcing itself.